Ag Marketing IQ: Key factors to watch in global politics and weather.

Hopes for a summer rally continue to fade as new crop corn soybeans grind lower with no threat of widespread damaging heat or drought on forecast maps. As major psychological support levels loom on the board – $4 corn and $10 soybeans – the only unknown seems to be whether harvest lows would come sooner or later.

The break was especially disappointing for soybeans. While corn typically fades after Independence Day, tops often come later for soybeans. But November soybeans for delivery this fall instead joined a race to the bottom with December corn.

So, with big soybean supplies looking more likely than not, what are the odds demand could spur a much-needed turnaround?

Definitive direction from the market may not come until well after the November election. But some signs should emerge soon, perhaps even before combines start rolling this fall. While USDA’s July 12 World Agricultural Supply And Demand Estimates paint a mixed outlook for the 2023-2024 marketing year ending Aug. 31, crush and exports are both forecast to increase during the upcoming selling season. Still, the twin pillars of soybean usage likely will have to exceed those expectations significantly to really affect prices much.

Adam Smith on the ropes

For the record, WASDE forecast a 5.9% increase in crush in the 2024 crop year, with exports rising 7.4%, taking total usage up 6.3%. While processors used more soybeans in 10 of the past 11 marketing years, exports are much more of an up-and-down metric.

If the hand of the market were truly free, price would dictate these flows, with a country’s market share depending on how much of a surplus they have to sell. But these days even the venerable Adam Smith fights with one hand tied behind his back. Politics in every key player in the soybean trade could affect buying and selling decisions, making predictions even more difficult in an industry rife with uncertainty.

Here’s a country-by-country breakdown:

U.S. tariffs and taxes cloud future

In the U.S. decisions loom for both soybean exports and domestic soybean oil demand. Tariffs are a question of how much, not whether or not they’ll be deployed in the war of words with China. Democrats and Republicans may not agree on much, but the Biden administration left Trump era barriers in place. Trump wants to supersize these measures if elected for a return to the White House, but Democratic moves to counter tensions over Chinese military and diplomatic initiatives across Asia, Africa and even South America could trigger retaliation that caused U.S. soybean exports to China to plunge in 2018-2019.

For soybean oil the unknown is much closer to home. More processing capacity continues to come online to support growing use of biodiesel. Margins improved this summer and lows earlier in the year stayed above seasonal lows seen over the past decade but alternative fuel’s profitability most of the time depends on tax credits and mandates.

The platform approved at the GOP convention last week doesn’t address biofuels directly, but is summed up by Trump’s catchphrase: “We will DRILL, BABY, DRILL” to expand energy production, while also ending “the Socialist Green New Deal.” That could end the type of support found in Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, while championing the petroleum industry.

Austerity squeezes Argentina, Brazil

Politics in key South American competitors could cut both ways. Free-market champion President Javier Milei of Argentina, in power for just over a half-year, has already followed through on promises to cut regulations and boost soybean exports from the world’s leading processor. Inflation, which was one of the worst in the world, has cooled dramatically, though prices ticked higher in June. Austerity measures are also fueling unrest in a country beset by poverty, where subsidies on essentials were once a way of life.

While farmers support Milei generally, the economic chaos could affect soybean acreage, expected to rise 2.4% in the coming year, though area would still be below levels from a decade ago.

Economic woes extend to neighboring Brazil, where even leftist President Lula da Silva is cutting spending, including changes in the tax code that could squeeze processors and farmers, perhaps affecting relentless expansion in the world’s biggest soybean producer and exporter. Little wonder then that Lula is wooing investment from China, by no coincidence the largest importer of Brazil’s crop.

China cuts U.S. slice

China, long the big dog in the soybean world, is looking a big long in the tooth, as it’s appetite for imports slows for the first time in a generation. In addition to structural influences, including an aging and declining population, China’s increases in soybean imports were tied to economic growth driven by exports. But growth is slowing and trade protectionism around the world threatens China’s exports, even as its Communist rulers met for a “third plenum” to address high unemployment, worrisome debt problems, slow consumer demand and the financial crisis in the property sector.

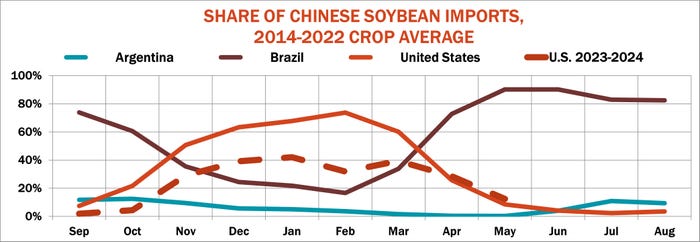

USDA projects less than a 1% increase in 2024-2025 Chinese soybean imports and that pie could include a smaller slice for the U.S. After sales eased in 2022-2023 during Chin’s strict COVID lockdown, it’s purchases this year account for around 59% of U.S. exports. But total year-to-data U.S. exports are down 16% from the previous year and sales to China are off 23%. Those numbers may be hard to adjust the rest of the summer, because China as usual is getting most of its soybeans from Brazil this time of year.

China’s purchases of new crop 2024 soybeans have only just begun, but U.S. forward sales to all customers are running at the highest level since 2019.

South America dries out

Weather conditions, especially in South America due to La Nina, may be causing some of those purchases. The emerging pattern of cooling in the equatorial Pacific is expected to be in full force by the time growers in the hemisphere begin seeding land for harvest in 2025. La Nina is associated with some of the biggest production slowdowns in the U.S., and also can disrupt South America, where drought is already present.

Fields here in the U.S. are in much better shape – the Drought Monitor last week cut the percentage of corn and soybean fields in drought to just 5%, the lowest readings of the summer.

New forecasts for August also out last week call for above normal temperatures across most of the growing season with dryer than normal conditions over the western part of the growing region. But even in these areas, dryness and temperatures aren’t expected to be anything extreme, with normal rainfall across the rest of the Midwest.

How much the big three exporters harvest is a key to exports. Politics aside, a country’s market share depends on its share of exportable supplies – stocks that won’t be used domestically. The U.S. share of those supplies is expected to fall to just 27% by the end of the marketing year in August, the lowest in at least 60 years, with only a 1% increase forecast for the 2024 crop. That’s one reason for the muted outlook for exports next year.

It also helps explain Friday’s finishing prices: a new low settlement for November soybeans of $10.36 and a close by December corn at $4.0475, just a half-cent off its bottom.